RICHMOND, Va. — How do you pick your heroes?

Much like my experiences in Columbia, S.C., showed me, Richmond is a city that has long had to reckon with its own heroes, especially with a past rooted in the Confederacy.

Perhaps “rooted” isn’t strong enough: This place was the literal capital of the Confederacy (moved from Montgomery, Ala., in 1861 with the strategic intent to use its iron resources and naval access). Today, and since 1890, Richmond’s Monument Avenue pays tribute to the figures (“heroes,” to some) who inspired and instigated Dixieland’s most infamous cause.

Take a look for yourself and you’ll see a Murderer’s Row of insurrectionists: J.E.B. Stuart, Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, and Matthew F. Maury. They’re riding horses, posing with swords, and generally doing the whole “look-at-me-I’m-so-tough” thing.

But one face in particular stands out from the crowd: Tennis legend Arthur Ashe, a black athlete and Richmond native who was excluded from many facilities (let alone tournaments) because of his race — before winning 3 major titles and becoming a pre-eminent face of representation and humanitarianism in the modern era.

But in February 1993, Ashe died of complications stemming from HIV, which he had battled privately for nearly 10 years. Doctors speculate that his diagnosis started around 1983, when Ashe’s second heart surgery (a corrective procedure) used an HIV-infected blood transfusion. News of Ashe’s diagnosis only became public in June 1992 when a personal friend who worked for USA Today called to verify if Ashe was as sick as the rumors suggested.

Ashe, refusing to appear weak, opted to break the news on his own in a public statement.

He died 10 months later, finishing his three-part book series on the history of the African-American athlete less than one week before succumbing to pneumonia, which he called a bigger achievement than any tennis win.

While the Confederate heroes on Monument Avenue stand poised, proud, valorous, etc., Ashe’s statue was added to the western end of the row in 1995, two years after his death, as he chose to be depicted: Suffering, gaunt, and dying. His bones are frail and his skin is tight. His clothes hang off of his wiry frame in the statue. He’s holding books and his beloved tennis racket, and he’s speaking to young children — extoling the virtues of intelligence and sportsmanship alike.

The addition of Ashe’s statue, of course, ruffled the feathers of “traditionalists” who did not want the sanctity of their slaveowners tarnished with…you know…a black guy who actually grew up here and did more for progress in his storied lifetime than they ever could hope for in 4 futile years.

But if you ask me what’s more inspiring: A bunch of fogey old white dudes who killed thousands of their brothers so they could own black men? Or an intelligent, stoic, well-written black man who died courageously, privately, as the whole world watched him struggle — afraid to appear either weak, or, stereotyped with a “gay man’s disease?”

That’s not even a debate in my book.

Recently, Richmond has continued the process of re-writing its history with a contemporary rhetorical response to what “heroes” mean today:

In 2019, the city unveiled “Rumors of War,” a massive bronze statue of a modern black man (with dreadlocks and a hoodie) riding a horse, directly echoing and responding to the row of Confederate statues on their equine mounts. The sculpture by Kehinde Wiley (known for his famous official presidential portrait of Barack Obama) was originally debuted at Times Square in New York City, and thousands of Richmond citizens assembled to welcome the new piece on the grounds of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Wiley said he was directly inspired to create the statue after visiting Richmond in 2016 and seeing J.E.B. Stuart’s horse-centric statue, and thusly modeled Rumors of War as a parallel response to it. Today, it sits on Arthur Ashe Boulevard, just a few blocks away from Monument Avenue.

At its unveiling, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam (who had a high-profile blackface scandal in 2019) said that “people in Richmond will recognize its shape and its form, but it depicts a person who looks different from every other statue in this city — and there are a lot of them. … And so today, we say welcome to a progressive and inclusive Virginia.”

Wiley himself said it in a more blunt way: “It’s a story about America 2.0.”

But of course, Richmond’s rhetoric when it comes to racial discourse and heroes has not always come with a ribbon-cutting or a statue reveal: After a 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Va., turned deadly — as well as the police murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 — the Lee monument was covered in graffiti, and many activists called for its outright removal. In October of last year, the New York Times deemed this public reaction “the most influential American protest art since World War II.“

In June 2020, the Lee Monument was unofficially repurposed with a citizen sign: “Welcome to Beautiful Marcus-David Peters Circle, Liberated by the People MMXX,” memorializing Marcus-David Peters, a Black man from Richmond who was shot and killed by the police in 2018. The area contained signs that told the story of Peters and lifetime/societal milestones he has missed since his death. The location is frequently used as a common protest site to remember all who have died from police brutality.

Today, the Lee monument sits behind heavy blockades (erected January 2021) to prevent more public defacing as the statue’s fate remains in question.

So what’s the fate of the Robert E. Lee statue? Well…

(Warning! Legalese ahead: Gov. Northam himself ordered the statue removed on June 4, 2020, but a state court blocked its removal pending the outcome of a lawsuit. The state court ultimately ruled in Northam’s favor in October 2020, but the decision was put on hold pending appeal. The Supreme Court of Virginia heard oral arguments on June 8, 2021. The Justices did not ask any questions during the oral argument. The Lee statue remains intact at this time, but the Lee statue in Charlottesville, Va., was removed about 10 days ago.)

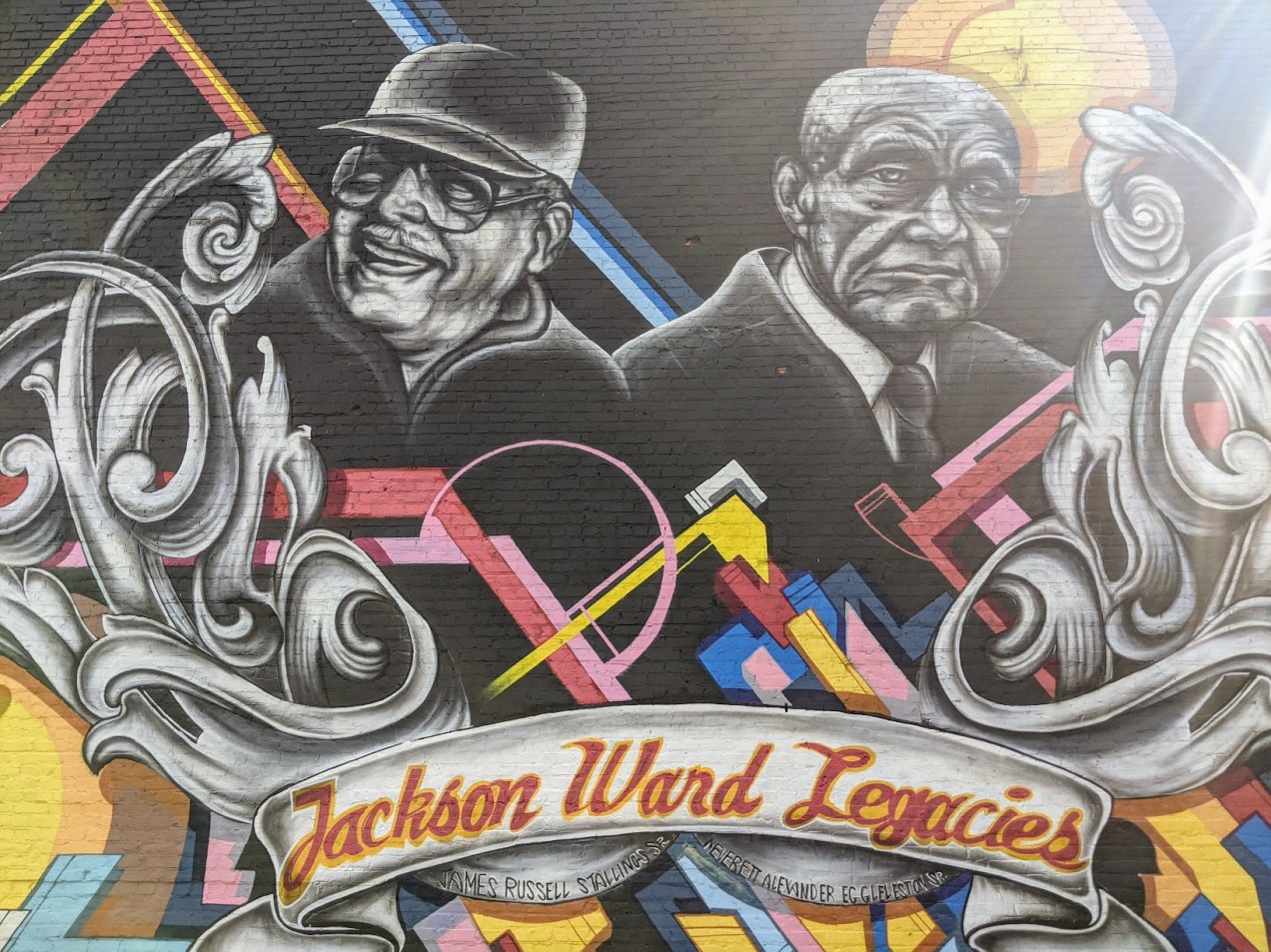

In addition to what I’ve said about Arthur Ashe and “Rumors of War,” here are some other key events in Richmond’s storied history of racial reckoning:

- In 1903, African-American businesswoman and financier Maggie L. Walker chartered the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, and served as its first president, as well as the first female (of any race) bank president in the United States. Today, the bank is called the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company, and it is the oldest surviving African-American bank in the U.S.

- In the first half of the 20th Century, Richmond native Bill “Bojangles” Robinson became the best-known and highest-paid African-American entertainer of the United States. Throughout his career, he used his fame to lobby presidents for more equitable treatment of black men in the military, founded the New York Black Yankees baseball team, and became the first black performer to appear in an interracial movie dance scene (with Shirley Temple in “The Little Colonel,” 1935).

- In 1990, Richmond native L. Douglas Wilder, the grandson of slaves, was sworn in as Governor of Virginia, the first elected African-American governor of any state in United States history. In 2004, he later returned to Richmond to serve as the city’s first directly elected mayor in more than 60 years.

The last thing I want this blog to become (though I would rest easy with the fate, should I get struck by a bus tomorrow) is a constant barrage of anti-Confederate thinkpieces — truthfully, there’s not much to think about — but that’s a hard fact I’ve learned during my first times in South Carolina and Virginia, respectively. I’m sure that the folks who live here would rather not have to think about the ugly truths of these men, either, but they’re plastered on nearly every corner as “heroes.”

But as I said in my post about Columbia, it is not just the right thing to do, but God’s Will, to continue to learn from our atrocities as people and ensure that our peers are treated with the dignity and respect they deserve, both in the now and in the future.

Richmond is a lovely place. It’s a poor place. It’s an opulent place. It’s a fatigued place. It’s a historic place with a rich arts culture. It still has much work to do in terms of figuring out how it represents its own legacy going forward.

But all of that is true about the United States at large — and I was privileged to spend this weekend visiting a distinctly American city.

And a city of heroes, at that.

###

-moose